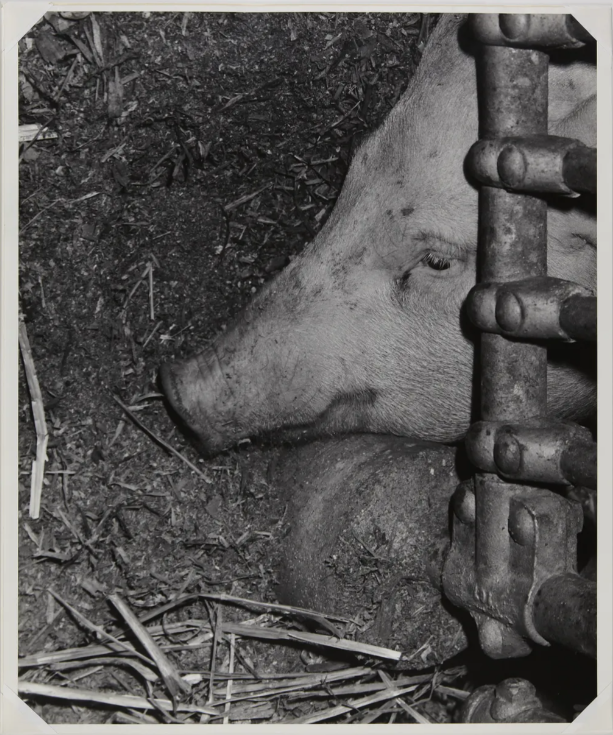

John Coplans’ Pig (1982)

Kudzu

Recent events have reminded me of this group of guys I knew in college and how they once bought a live pig to smoke and eat, but ended up doing neither, and instead brutally killed it in their backyard after several torturous hours of not knowing what to do. They were part of a campus ministry I was loosely involved with, and they lived together in a house just off-campus that was subsidized by that same ministry. I say “loosely,” but I was as a part of the day-to-day as anyone—playing guitar at worship nights, prayer retreats during our school breaks, small group. I even led one of these small groups for a time in the book of Romans, “I do not do what I want to do,” etc. But there were some things I was oblivious to at the time that make it seem strange for me to now say that this was all something I was a part of, that I lived in.

So. “Loosely.”

I have no idea how they got the farmer to agree. You hear things about how farmers still care about the animals, give them “only one bad day,” but whoever raised this pig didn’t care. Who would let anyone put a pig in a cargo trailer? Who sees these idiots roll down the door and throw the latch and thinks it’s a good idea?

They had to take backroads, to make the careful drive back into Chattanooga, where we all lived, losing our faith and killing time. They parked in the alley behind the house and led the pig into the backyard with a rope. The knife and other tools—a bucket, gardening shears—were on and around a plastic folding table. They tapped the keg.

The pig knew. It went to a corner of the yard and nuzzled at the pressure-treated pine, looking for soft spots, and moaned.

The boys got a little queasy. Jordan—the only one I really remember, and the one most people focus on whenever this story gets told—was the brains behind the whole thing, but even he started mumbling about how he wasn’t sure if they had the right idea, if they really knew how to go about it.

He suggested they watch the video again.

They huddled around one of their phones, tilted sideways, to rewatch the YouTube video they’d been working from. They sucked on long necks and sipped from plastic cups and watched a man much older than them explain that, even if you don’t have a captive bolt device (what is typically used to kill animals in slaughterhouses), you could crush the pig’s skull with a sledgehammer or rock, as is done in remote parts of the world without access to more industrialized means of slaughter. “Where ammunition is expensive, or can’t be spared,” the man on the video said, “but unless that’s your situation, a firearm is best.” Someone in the huddle reminded everyone that they had talked about wanting to keep the skull intact and put it on the kitchen island with an apple in the teeth, and then afterward walk around with it, like it was their own head, and they all nodded. The man in the video suggested a firearm appropriate for small game, with at least a twenty-two caliber round. He said a shotgun would be best. This is where there had been some dispute, as they had agreed not to use one of the shotguns they owned because someone would inevitably hear, and the group had found out recently you needed all kinds of permits for something like this, even if you aren’t shooting it, which they didn’t have. They also knew that they weren’t going to be able to hang it up before cutting its throat because then the poor thing would really know what the score was, would scream and alert the neighbors, get them in trouble, etc., and they couldn’t afford a fine, as the pig itself had cost nearly four hundred dollars.

“I thought you said we could tackle it,” one said.

“No way, I said we should use the knife,” another said.

“That’s what I’m saying. Get it down on the ground and do it. Right in the head, like this.” The guy speaking poked his forehead, then thrust his hand down, burying the blade of an invisible knife in the palm of his other hand.

They looked up from the video of the man explaining why a tractor, though preferably a back-hoe, would be the best option for hoisting the carcass up for bleeding, and looked at the pig.

The pig looked back at them as it leaned on the fence. It was eight-thirty in the morning. Everyone was arriving at six.

“We have to do something,” one of them said, picking up the knife and walking over to the animal. He threw his arm over its shoulders and tried to hold its head in place as he raised the knife, blade down, but it screeched and bucked and knocked him off and into the mud before scurrying over to the back porch and, strangely, sidling up behind one or two of the others guys, almost, it seemed, in the hopes of being protected.

“You can’t show the knife,” Jordan said. “They tense up. It’s bad for the meat.”

“So what? It’s fucked?”

They wondered if they should cut their losses. Possibly return it.

“Bullshit.”

“Everyone’s coming.”

“We could order something.”

They had no idea, or had forgotten, or had drunk enough to forget had it been said in the car or earlier or even whispered right then and there, amidst the decision-making, that cooks like this, a whole hog barbecue, often take days.

“We could keep it.”

“And it would live in the yard?”

“Has anyone ever done that? At this school?”

“We’d be the first. And that’s cool. Like we’re the guys with the pig.”

“It’s too late,” Jordan said, walking over and taking the knife. “Pin that thing down.”

The boys chased the pig back into the open yard and formed an oblong shape and closed ranks around the one-hundred pound animal, which whined and oinked as it ran in smaller and smaller circles, until they had all surrounded it and were able to stand beside it like pall-bearers and grab its ankles and spread them out and try to push it down onto its stomach in the mud. Jordan brandished the knife as the thing squealed, thrashed, and in a desperate act to get it to shut up, he stabbed at it awkwardly just below its jaw.

The cuts were deep, but far from anything that could kill it, and it was enormously strong, and it hurled the red-faced upperclassmen off itself and limped away, a trail of blood following it, still screaming.

If you haven’t heard a pig scream, it sounds like a woman if a woman could scream as loud as a jet engine. It could strip paint off a car.

Jordan went inside to get a gun, and found a shotgun propped up against a bathroom sink on the second floor.

He walked up to the now stationary and coughing animal and pumped the shotgun, saw the red shell in the chamber, steadied himself, let the animal search his face for his eyes, and at the moment the pig looked at him, truly looked at him (I’m editorializing here), he pulled the trigger.

He fell to his ass and hit his head on the ground. Disoriented, he sat up to witness the carcass, but the pig was still not dead. Slumped down now, on its side, shaking and wheezing out frothing blood between its brown teeth, with about a million shallow holes in its face. The gun had been filled with birdshot, and though Jordan had shot it very close, this had just stunned it. The blood must have been from what he had done with the knife.

The group gathered around. They stammered and shouted at each other. Then they took turns hacking away at the throat, with Jordan sitting just a few feet away holding the gun, until the thing finally stopped moving, and released its last farty breath, and began seizing. When it stopped, they tied the rope to both of the animal’s ankles and threw the rope over a branch. The branch broke at their first coordinated pull.

Soggy weather. Leaves laminated to the ground by the previous day’s rain and now blood. They took a break around the keg.

Jordan washed his hands and walked out the back gate into the alley, looking for signs that what they had done had been heard, recognized, understood, and then around to the street, where he continued up and down. A man was sweeping off his front porch and the two made eye contact, once, twice, again, until the man stopped and stared. Jordan took his hands out of his pockets and jogged back to the house.

“I think we’re clear. I think it’s fine,” he said to a couple of the guys, sitting on the couches, watching the NFL combine.

“You should see what’s going on back there,” they said.

In the backyard, a couple of the guys had been using the gardening shears to pierce the animals belly and pull out the guts, but in doing so, they had burst the stomach and intestines, and, to clean up, had turned on the hose and were trying to push everything—the fattened liver, the deflated lungs, and endless rivers of red and yellow water—out of the abdominal cavity by using the “jet” setting. One of them threw a slob of bile at another. Someone said it smelled like the operating room of his father’s veterinary practice. Another said, no, the third floor bathroom when it's hot outside.

“The fire,” Jordan said. They were supposed to have started it as soon as they returned. They’d tried to get someone to stay and start it, but everyone had wanted to go down and get the pig. Jordan walked over to the U-shaped cinderblock construction they’d set up the day before, and removed the tarp and fingered the now damp wood that they had left on top of the chicken wire platform where the pig would lay.

He sent one of the least drunk out to get more firewood. He bundled Amazon cardboard and paper grocery bags and put some of the damp logs on top. He cut open the lighter fluid bottle from the side with his pocketknife and dumped the whole thing on the pyre, lit it, and watched. Green and blue flames licked the wires.

“Don’t we need to skin this thing?” one of the ones spraying the guts asked.

“No, the skin is the best part.”

“What about the hairs?”

“Those burn off.”

“Ew, seriously?”

Jordan told them to grab it by its front legs and drag it over to the cinderblocks. They still had almost all of the guts to scoop out.

“You have to cut them out,” Jordan said, watching the fire, but walking over to the animal. He knelt to the ground.

The sounds of noodles slipping against each other in a pan, but louder, as the flames died out, the bags and cardboard burned to ash, the logs darkened from the fire, the smell of iron.

Jordan washed his hands again and called the guy who’d been sent to get the wood, but no one answered. He called a few more times.

Waiting around. Three to six beers passed. Maybe eleven, noon, at this point.

There wasn’t much else to do.

They threw the tarp over the animal and left it out for a couple days. They returned the U-Haul because they didn’t want to pay for more than twenty-four hours. They shoveled some dirt on it, made a bit of a mound, but not enough. Animals most nights, cats in particular, but also possums and skunks, came and nibbled at the body. I remember that night we all got texts to meet at a bar downtown, that the barbecue was off. The guys didn’t say anything then about the carcass beginning to rot in their yard. They also kind of made it sound like they were going to buy us dinner, or at least a beer, but when we got there, they had already ordered food and pitchers for themselves. and we all ended up getting separate tabs. It wasn’t until months later that any of us found out the truth, which I’ve pieced together for you here, as best I can.

They had lost interest, is the only way to put it. Probably way earlier, they just didn’t know it at the time.

I’m telling you now because, about a decade later, I told my new boss an abridged version of this story in response to something she had said while she was training me on the office’s methods for record-keeping. She was rambling a bit about being responsible, taking ownership for your mistakes. “It is very hard to find someone who actually wants to get better, who actually wants to try,” she said. I was nervous and said something like, “Oh I know. I know. These guys I knew, they didn’t do that, and they, well—it was bad,” and she swiveled in her chair away from the spreadsheet we were looking at to look at me, and I fumbled through the story, not thinking about what it was I was saying, and she stood abruptly, putting a hand to her mouth, pushing past me and running out of the office. I stared at the spreadsheet on her screen, which had to do with tracking payment for our office’s expenses, everything from paper and staples to years long contracts and catering, and waited.

When she returned, she paused in the doorframe. “I know this is a new environment for you, and I want to be understanding, but that wasn’t appropriate.” I agreed completely, apologized profusely, and she sat back down and we continued to look at the columns of invoice codes. As she described the problems with the person who previously held my position, how this person had refused to ever take any form of accountability, I got a text from my wife saying, “Frank bit Basil.” Frank is our dog, and Basil is our son, so I began typing, “It’s my first day,” but she texted back, “He’s fine, but now, especially after my grandmother, I think we need to surrender her,” just as my boss asked me a question, something about whether I would want to continue with this system or institute my own, so I put my phone down and folded it in between the pages of a packet of lists and instructions she’d handed me, and asked, in the tone and manner I’d practiced in mock-interviews, “Sorry, I just received an automated email from HR and thought it was important. What were you saying?”

Sometimes, I wonder if this story with the pig is even true. Even as I tell it, I see the inconsistencies. How could they never have been found out by anyone? What about the smell? You also don’t want it to be true, and therefore imagine all kinds of things. The pig never died, maybe, because it was rescued by a neighbor. It was returned to the farm! Or it had been thought to be dead, but days later had gotten up and shaken off the tarp and waddled into the alley sunset. Or maybe it really had been dead, and then somehow not.

Jordan’s the one who is remembered when this story gets told because he became, of everyone I knew from back then, the most famous. After college, he was kind of a big deal in the church that led the campus ministry. He wrote the Goliaths that America’s youth face—anxiety, social media, pornography—and their hunger for something real. He started a podcast. He was what they call a “thought leader,” and hopped around to different churches, becoming a bit of a minor celebrity. “He’s just so in the Word,” you’d hear people say. “And he gets down on their level, you know? He understands what these kids are going through.”

Some accusations came out, texts with girls in the youth group, some as young as fifteen, but while what he had done was deemed “spiritually inappropriate,” it was not technically illegal. This allowed him to rebrand into a different kind of leader for a different kind of church. Every crisis in his career has been a transition, a pivot. He has one of those houses that’s all white inside, like a hospital. I’ve watched since-deleted videos where he sits in a lawn chair behind his house, the sun high above him, his hat on backwards, as he recites scripture that references swords and war and weakness. I’ve read the comments, the ones suggesting that you don’t know Jesus if you can’t forgive this man, and the ones saying he is exactly who Christ would condemn. And I think about that pig, and now my own animal, one I thought would be so easy, but that has now become impossible.

The senior dog shelter is in an old house two towns up a state highway. We walk through it, my wife and I, and the owner shows us all the other unwanted dogs they’ve taken on. Big fat white ladies lay inside of gate-partitioned sections of what used to be a living room, stroking the backs of whippets with missing eyes, chihuahuas too arthritic to walk. The director, with snow-white dreads and wire glasses, introduces them all by name—Bully (pit), Boxcar (black lab), Muffins (kelpie-pointer), The Undertaker (teacup poodle). She says that, based on Frank’s history, even with the biting, which she believes is actually herding, they feel good about her integrating into the group.

“Can we visit?” my wife asks.

The director gives us a knowing look.

“Probably not good for her,” I say.

The director shakes her head.

We go back out to the outside play area where we left Frank, and she’s still at the gate, jumping at the latch. We say thank you and shake hands. We’re told they’ll be in touch soon.

On the highway, we shout at Frank to lay down. She whines. Hate to say it, but we shout louder.

We come back in a week with our son, who has just turned two. We take Frank on one last walk on the path that snakes around the house’s property, which goes past a lake, shimmering with dragonflies. Every fifteen steps, Basil walks over to Frank and hugs her neck. When he does this, she stands absolutely still.

“Frankie, that’s okay,” Basil says when he stands up straight. “Okay, that’s okay, Frankie. I’m not mad. You’re okay.”

The team takes her upstairs to help with the transition. We walk slowly through the lot after, weighed down by the wet heat of deep summer and the yawning, insect “ahhhhhh.”

“We go see Frankie,” Basil says from the carseat. “We go see her. Bye Frankie.”

“We’re not going to see her again,” my wife explains. “She lives in that house now.”

“Oh,” he says. He puts his fingers in his mouth and looks out the window.

If we were still the kind of people who prayed, this would be the time to do it.

We pull back out onto the state highway. Eighteen wheelers ahead of us kick up dust for hundreds of feet. A mile goes by and my wife asks where we want to eat.

I say, “I was thinking—”

But we hit something. It thunks the bumper and we ka-thunk over it. I swerve but remain in control, and pull over into the shoulder.

The dust flares and whips in the wind as I walk down the shoulder to see what it was. The half-light of evening catches tiny specks of sand, making them like glitter.

When it dies down, I see a black plastic trashbag, like a giant, deflated heart, split down the middle with its insides—what appears to be old couch cushions—littering the road. Some of the cushions are also split, and their white, synthetic stuffing blows down the road. There is a mountain of other garbage just behind me in the brush, I discover, which are split too and spilling out other household items—bed frames, lamps, nonstick pans, etc.

It’s such a waste.

Jordan prayed a lot. Publicly. At the bar, the failed dinner, he insisted we say grace, which he led.

“Like…God,” he prayed, head bowed low as a server hovered behind him, holding plates of chicken fingers. “Please just be here with us, you know? Like we need you right now.”

My wife had been there, though she wasn’t my wife at the time. Not even my girlfriend or anything. In fact, that was the night we met. And look where we are now.

We got together a few months later at a party at that same house. We kind of lost control, forgot what we believed. There were many dark corners you could go to in that house and use to do what you knew you shouldn’t. This was the unspoken understanding, why the parties were held in the first place.

“Mouth,” I remember her saying, on the second level of a three-tiered bunk bed made out of two-by-fours, chicken-wire, and futons. I wrapped up the sheet after and washed it at my apartment and shoved it into the guys’ mailbox a week later.

We cried, if you can believe it. We held hands in her living room while sitting on two separate couches and asked God to give us the strength to never do anything like that again. But we did, and we prayed again, too.

At another one of these parties, Jordan told me everything. Every detail of his and the boys’ Easter failure.

“Here,” he said, toeing at the dirt just off the concrete slab at the back of the house. The tarp still lay there, though it was partially overturned, with a black, organic stain on its underside.

“Where did it go?” I asked, drunk.

He laughed, drunk. Light rain fell in front of us. Music thumped behind us. He took out a cigarette.

“To dust, she returned,” he said and laughed again.

My boss is funny. She sees personal information as a liability. It’s all innuendo with her. Arms length.

She’ll sigh and go, “But that’s my own thing that has to do with something else,” after a long conversation about systems that don’t work, her specific disappointment. A waving of a hand at “something else,” usually to the air behind her.

And when I go, “Yeah, we all come to these situations with stuff. Like, back in college, I used to really believe…” or “It’s a really a shame that…” or “I definitely still see the value in…”

That’s when she’ll look at her watch.

Frank had been a gift, from me to my wife, a week or so after we’d returned from our honeymoon. It was meant to be practice for a baby, but when the baby came, we essentially imprisoned her, furious that after our sleepless nights of bottle-feeding and endless there-there-ing, this stupid dog still wanted to walk, run, not be in a cage. We held on for a while, wanted to make it all work. But it was too much.

Since giving her up, I’ve been going to some of the churches around here. Not every week, not always on Sundays. Just popping in, shaking a hand. Letting someone sing for me and being around to hear it.

We moved up to the northeast a few years ago, to be closer to my wife’s family. A lot of the old churches have been converted into mixed retail, or co-working spaces, offices, and their spires are now done up with these 5G receivers. Add that to the list of things slowly changing in our backyards, one reality melting into another in a way that feels like nature the way you hardly notice, don’t even know how to resist. Like kudzu.

That’s also what I think about when I remember that town in the valley of Southeast Tennessee, where I would drive through the thick, rampant growth between suburbs and feel like every vine-smothered tree and speed limit sign and headlight around a blind corner was illuminated, channeling some spirit or deep, abstract reality behind things, filaments of flickering truth.

Even as I explain all this to you, that green is still spreading across the inside of my skull.

Calvin Cummings is a writer from East Tennessee. His work appears in or is forthcoming from Haskell Industries, Soft Union, Blue Arrangements, and elsewhere.