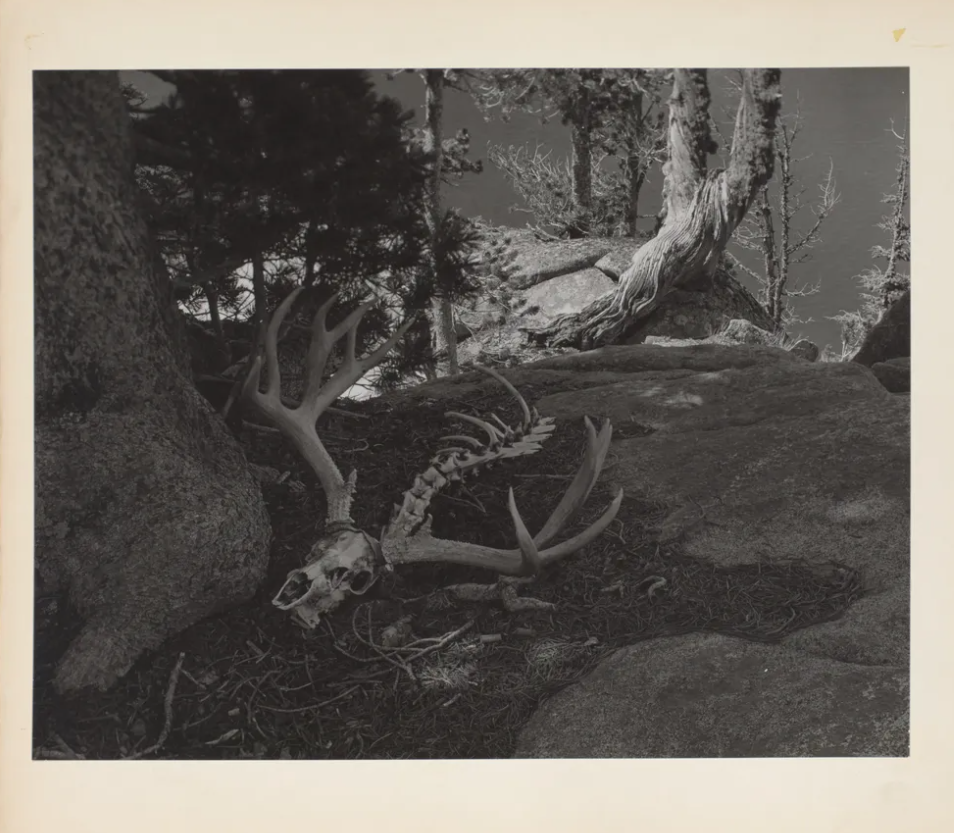

Minor White’s Steamboat Lake, Oregon (1941)

Pet Sitter

The day of my interview, a woman hung herself from the overpass above me as I waited for the M6 bus. I should have taken that as a sign, but my money was running out. The ad I responded to was for a dog-walking job with a pet sitting company.

As I spoke to the manager, a small dog ran circles around us.

“Cats?” she asked.

“I love cats.”

“Dogs?”

“Grew up with dogs.”

“Guinea pigs? Snakes?”

“Love em.”

“Birds? Little birds. Parakeets. We don’t have any parrot clients. Yet.”

I started to suspect this interview wasn’t really necessary.

“I love birds.”

“How are you with needles? We’ve got two diabetic cats on the roster.”

She wanted me to start right away. My first job was pet sitting for somebody named Abe. He was out of town for two weeks.

His house looked haunted from the outside. When I tried the knob, the door was already unlocked. The air smelled stale.

I walked inside and there was a girl in there, standing by the kitchen sink. She was holding a syringe in her hands. I could see little dark clouds of fruit flies around her, attracted to the pile of rotting crabapples on the counter.

She looked up at me and almost dropped the syringe.

“Sorry, I didn’t realize somebody would be home,” I said.

“I’m just the pet sitter,” she said. She pointed to an obese cat on the floor. “Oh. Taryn said I was supposed to be here, though,” I said.

“Maybe that was a mistake,” she said.

“I talked to Taryn yesterday. I told her I was good with needles. She told me to come.” “Okay, well. I already did this one. So you can do the other one,” she said.

I squeezed the cat’s neck rolls together and stabbed it. The cat seemed unbothered. I pressed the insulin into it and let it go. The cat looked up at me and I looked away.

“Is that all we’re supposed to do?” I asked.

“Well, I fed them, too.”

“So we’re done?”

“Yeah. But hey. I need this money. Can you ask Taryn to put you on a different job?”

I walked home instead of taking the bus, because I wanted to smoke cigarettes. I didn’t call Taryn, even though I said I would. I thought maybe she’d realize her mistake on her own, scheduling two employees by accident, but she didn’t. I liked the tension it created, so I showed up to Abe’s the same time the next day.

The girl was in the kitchen again. This time her hair was up and slightly wet, like she’d just taken a shower before she arrived. She laughed when she saw me.

“Dude.”

“Hi.”

“Why are you here?”

“I don’t know.”

“You don’t need to come by. I think you were scheduled by accident,” she said.

“Yeah, I know.”

There was a long silence.

Finally,

“Okay.”

All of a sudden, I was embarrassed I’d shown up.

After we took care of the cats, we sat in Abe’s backyard together. There was only one chair. It was made of wood and it looked like it was rotting. I let her sit on it, and I sat on the ground.

“This guy is weird,” she said. “Everything in his house is broken.”

“What do you think he does?”

“He gets VA benefits. I saw. He’s in AA, too.”

“How long have you worked for Taryn?”

“Like six months.”

“Oh. I just got hired.”

“She hired me as a dog-walker, but now she wants me doing this stuff.”

“Do you like it?”

“I like seeing people’s houses.”

She drove me home after that. Her car was a 2017 Subaru Forester with a broken passenger side door. She told me it broke when she got T-boned at a four-way intersection on her way home from traffic court for unpaid speeding tickets. The other driver drove away before she could even pull aside to park. The backseat was filled with assorted layers of junk; sports bras and dirty beach towels, gym shoes, a Stetson cowboy hat. She wasn’t self-conscious at all about how dirty her car was.

When she got close to my house, she slowed down and unlocked the doors. I got out.

“See you tomorrow,” she said.

I went inside and sat on my couch and waited for tomorrow.

The next day, we explored the second floor of Abe’s house. It was damp up there and smelled like a wet picnic table. None of the light switches worked. Every bulb was burnt out. There were giant paintings propped against the walls, framed but never hung.

“Do you think he painted these?” she asked.

They looked amateurish.

“Maybe,” I said.

“Do you make art?”

“I take photos. But I haven’t taken any in a while.”

“Why not?”

“I don’t even know what looks good anymore.”

“My mom’s boyfriend is a photographer. He makes these calendars with the photos he’s taken from each month, and plugs them into this app, and prints it off this website. He makes them every year. But he always chooses really bad photos of us. To him, they must all look the same. I think that’s why he’s a bad photographer.”

“Do you make art?” I asked.

“No,” she said. “Just money.”

She didn’t ask me many questions, but I preferred it that way. If you’re a good listener, people just start confessing things to you.

She didn’t say anything crazy, though. She just said normal stuff about her life. “Can I see some of your photos?” she asked.

“Maybe later.”

“Not tonight?”

“Not tonight.”

That night I didn’t sleep. And I didn’t show up to Abe’s the next day. I didn’t really feel like doing anything.

The day after that, I went back to the house. She wasn’t there. I wasn’t sure if she’d been there already, or if she’d come by later. Either way, I didn’t feed the cats, and I didn’t give them insulin. I was technically off the job, anyway, so it wasn’t my responsibility.

I looked for her in the backyard. There were crabapples everywhere. The trees were all crooked. It reminded me of a cemetery.

I took the bus home.

At home, I got a call from Taryn, telling me there was a scheduling error and I wasn’t on the Abe job anymore. Instead I was supposed to care for a bearded dragon whose owner was in Florida. She asked me to drop off Abe’s keys.

I realized God was closing the door on me.

I went back to Abe’s that night, after the sun had set. His door was still unlocked.

Inside, one of the cats lay motionless on the ground. The other one was standing up, watching me. I opened two cans of wet food, and the cat on the ground didn’t move. His eyes were open, but his body was stiff.

Why didn’t she show up today? Was it because I had stayed home the day before? Maybe she thought I was uninterested. That wasn’t my intention at all. I felt I needed to set things right, but I didn’t even know her name. I put a bowl of wet food on the ground and scooped the frozen cat into my arms.

I searched the streets for a Subaru Forester with him cradled to my chest. I didn’t see one anywhere.

I walked to an animal hospital at the edge of the neighborhood. The employees took the cat from my arms and hid him away in a secret room. I asked how much this was going to cost, and they couldn’t tell me. They couldn’t tell me anything.

I said I was going to step outside for a cigarette, and I walked back to Abe’s. Everything was bigger than it was before, and more evil. I threw away the crabapples on the counter. I went upstairs and hung the frames in total darkness. When the sun rose, I left for good, and I locked the door behind me.

Emmy Daniels is based in New York. Her writing has been published in 2x2, SWAMP, and elsewhere.